Liu Bolin. Hide and seek

Curata da Francesca Tarocco

Dal 08/11/2008 al 10/01/2009

Galleria Boxart, Verona

Galleria Boxart, Verona

Liu Bolin, tra illusione e realtà

di Beatrice Benedetti

L'arte è mimesi, scrisse Aristotele.

E se l’arte imita il reale, l’arte non può "mentire", come per Platone, ma punta dritta al piacere e alla conoscenza. Sofismi a parte, se inganno ci dev’essere, è un inganno che fa crescere.

A miglia - e millenni - di distanza, rispunta oggi la diatriba sul valore dell’arte. E si riverbera nel fervore creativo della Cina, grazie a un artista che avrà letto sì e no i nomi dei Padri Filosofi dell’Occidente.

A ben guardare, infatti, i camaleontici ritratti di Liu Bolin (Shandong, 1973), frutto di accurato body painting e gioco prospettico, riconducono quasi di getto alle dispute della Scuola di Atene. Qui l’arte imita senza equivoci la vita e le verità universali si (s)vestono del loro abito confuso col reale.

Beatrice Benedetti: Iniziamo dalle tue foto più note, quelle della serie "Hiding in the city", dove il mondo inghiotte uomini e donne, compreso te stesso, erodendo loro spazio vitale. In questa sopraffazione è forse l’arte l’unica via di fuga?

Liu Bolin: Gli scatti che ho concepito per la prima volta tre anni fa (quando fu raso al suolo il villaggio di artisti Suojia dove viveva Liu Bolin, ndr) si prestano a una doppia lettura critica. Da un lato, è il mondo moderno a privare di spazio fisico e mentale l’uomo. Ma è anche vero che nella maggior parte delle mie foto il soggetto sono io. Di fatto io stesso scelgo di apparire in quel determinato contesto, immergendomi in esso.

B.B.: Vuoi dirci che non si tratta di subire senza scampo l’aspetto alienante del progresso?

L.B.: Esatto. Se così fosse, avrei deciso di dipingermi, che so, tutto di bianco, o tingermi di un colore in contrasto con lo sfondo. Invece, simulando il mimetismo degli animali, ho voluto dare l’idea di appartenenza al contesto in cui sono nato e che mi contraddistingue.

B.B.: Il "milieu" connota fortemente l’uomo. In Europa ce lo dissero una volta per tutte gli scrittori del Naturalismo e del Verismo. L’effetto collaterale avviene quando l’ambiente impedisce lo sviluppo del pensiero autonomo. Tu stesso denunci il caso limite del totalitarismo comunista che ha segnato la storia cinese, definendo le tue performance "social sculptures", sculture viventi dal contenuto sociale.

L.B.: Certo. Io però ho scelto di vivere inserendomi e assecondando il mio mondo, lasciandomi proteggere da esso. E’ più facile così, se si vuole.

B.B.: Però in Cina alcuni artisti "non organici", come i tuoi amici Gao Brothers, pensano che si debba remare contro per sfuggire a certe vessazioni, evitando di essere accondiscendenti.

L.B.: Io non la penso come loro. Non voglio andar contro l’autorità del governo. Non servirebbe a granché, tra l’altro. Il potere è di chi comanda. Non credo che per cambiare le cose si debba per forza essere "contro".

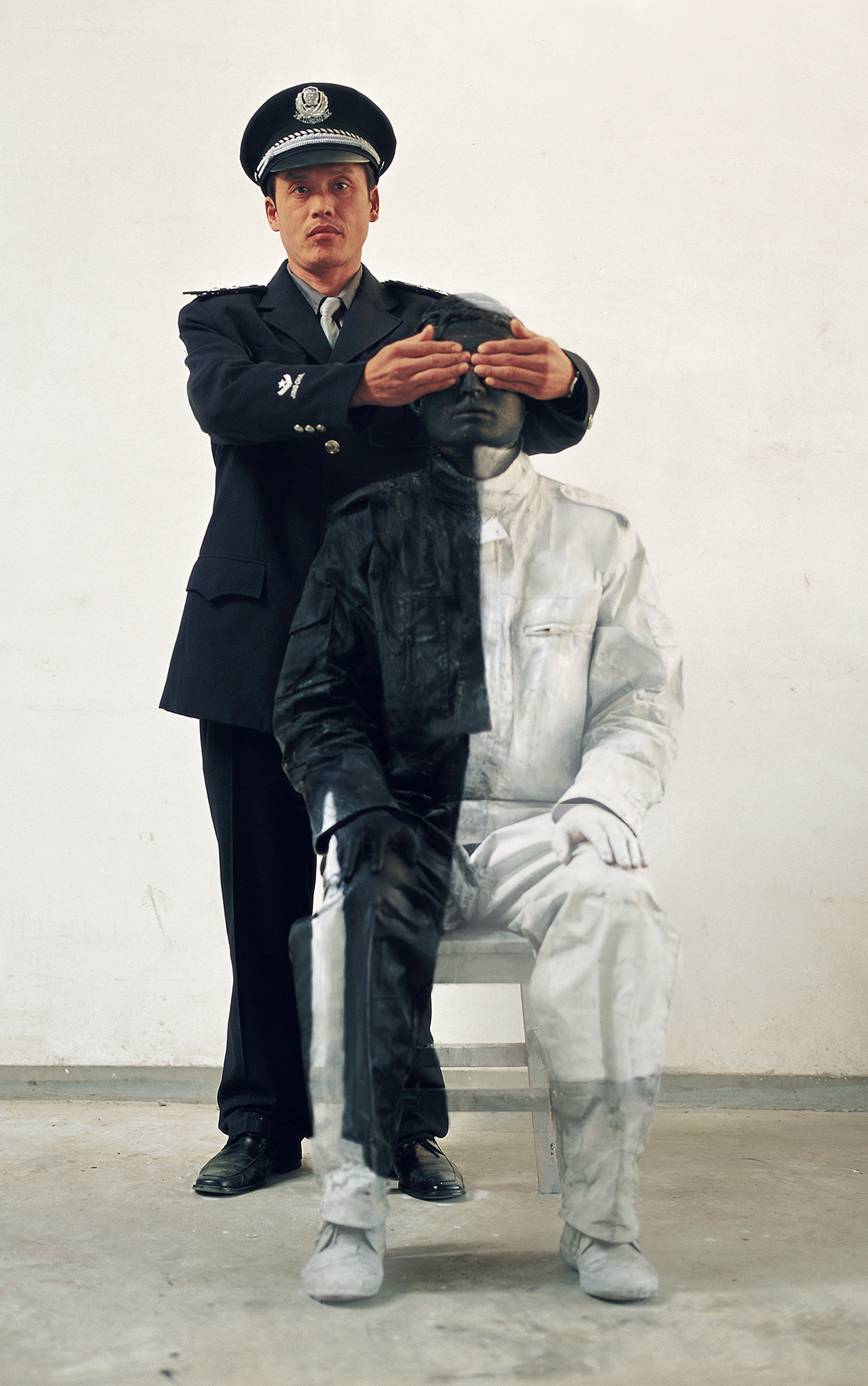

B.B.: Come la mettiamo però con sculture come "Fist" (2006), un pugno in bronzo che simboleggia il potere oppressivo, o "Red Hand" (2006) in cui una processione di uomini in divisa si coprono gli occhi a vicenda con mani rosse, colore del partito oltre che della violenza?

L.B.: Il rosso è il colore della Cina stessa. Io nasco come scultore (alla scuola di Sui Jianguo, ndr) prima che come fotografo e performer. Quei lavori sono fondamentali e campeggiano al Distretto 798 di Pechino. E’ vero, il pugno, in tutte le varianti che ho realizzato, simboleggia il potere oppressivo, che viene dall’alto e schiaccia chi sta sotto.

B.B.: Appunto, un messaggio inequivocabile.

L.B.: Sì, la comunicazione è immediata. Ne ho avuto la certezza un giorno, passando davanti alla mia scultura in bronzo al 798. Ho notato un anziano che si faceva ritrarre in foto dalla moglie sdraiato sotto il pugno. Ho capito che non ero stato frainteso, il messaggio era chiaro. Nel 2006 ne ho fatto una performance per l’inaugurazione in una galleria cinese con uomini e donne distesi sotto il pugno rosso (Red Hand, 2006).

B.B.: La polizia non deve averla presa bene...

L.B.: In realtà finora non ho mai avuto problemi di censura coi miei lavori.

B.B.:Forse perché le tue opere hanno una componente poetica che ne alleggerisce in qualche modo il messaggio?

L.B.: Può darsi. In Sunflowers (2008), ho rappresentato il potere della sovrastruttura che impedisce un pensiero autonomo. Il girasole si orienta sempre verso un sole che proviene dall’alto e gli da nutrimento. In Sunflower on the table (2008) i girasoli nascono come individui malformati seduti su una sedia della dinastia Ming. Un simbolo inequivocabile che rimanda alla Cina.

B.B.: “Leaves on the man”(2008) segna la via di mezzo in questa trasformazione.

L.B.: Sì, più che un uomo, in questa scultura ho ritratto un bambino, sul quale la pressione dall’alto viene esercitata mentre è ancora un feto, e riceve ancora il nutrimento dal vaso, dalla madre terra. Burning man 2 (2007) rappresenta infatti una madre che tiene in braccio il suo bambino e già lo plasma, ne forgia il pensiero.

B.B.: Capisco. La sai lunga, denunci il plagio della mente con mezzi “soft” che sfuggono al controllo del regime.

L.B.: Qualcuno però se ne accorge. L’editore del mio catalogo monografico non ha voluto pubblicare la foto in cui sono ritratto al posto dell’effigie di Mao in piazza Tien An Man.

B.B.: Forse è stato meglio così, almeno non ti sei compromesso. Poi la foto l’hai stampata per la tua prima personale in Italia “Hide and Seek” vero?

L.B.: Sì, esiste anche in Francia.

B.B.: Però, perdona il campanilismo, è l’Italia che ti ha stimolato un lavoro inedito.

L.B.: Proprio così. Ho trascorso a Verona le tre settimane che precedevano la mostra alla Galleria Boxart e ho deciso di concentrarmi sul patrimonio artistico che è la base della cultura italiana e viene conservato. In Cina, invece, tutto si rinnova con un colpo di spugna. Non solo per le imposizioni del governo, che con una scritta su un palazzo lo demolisce per sempre. E’ la gente comune a preferire il cambiamento, anche a costo della distruzione necessaria.

B.B.: Finora un modo di agire vincente, considerata la rinascita economica.

L.B.: Sì, staremo a vedere. Del resto io sono un artista. Alle gallerie compete lo studio dell’andamento del mercato. Il compito dell’artista è quello di superarsi sempre, con il proprio lavoro. Per il resto, a me interessa una vita dignitosa: una famiglia normale e il necessario per vivere.

Liu Bolin: vedere con il corpo

Zone di libertà?

Francesca Tarocco, Shanghai 12 Novembre 2008

Esattamente come il suo skyline, l’arte cinese cambia a ritmi assai rapidi. Ma quando sono emerse per la prima volta le strategie espressive che dominano oggi la scena dell’arte cinese e quali sono le sue caratteristiche di allora e di oggi?

Il ruolo della prima mostra sperimentale in Cina è convenzionalmente assegnato a uno show organizzato dallo Stars Group (“Gruppo Stelle”) il 27 settembre del 1979 in un parco nel lato est del Museo Nazionale d’Arte Cinese. Gli iniziatori del progetto espositivo erano Huang Rui e Ma Desheng e i partecipanti includevano nomi ora celebri, quali il curatore Li Xianting, l’artista concettuale e architetto Ai Weiwei - ancora oggi attivi- nonché i celebrati poeti Bei Dao e Mang Ke. Fu un’azione spontanea. Non c’erano sponsor, né opere in vendita. I lavori esposti erano stati scelti per la loro originalità e non erano stati ufficialmente approvati, né contenevano alcun tipo di propaganda politica. La mostra fu chiusa quasi subito, il 29 settembre. Si trattò solo di una tra le molte esposizioni che offrirono ai fruitori occidentali della scena dell’arte contemporanea cinese uno degli scenari prediletti: quello che vede gli artisti visivi impegnati in una battaglia costante contro presunte autorità repressive. Ciò non vuol dire che non esista una censura o l’intervento dello stato in campo artistico in Cina. Tuttavia, la situazione era, allora come oggi, assai più complessa.

Un momento nuovo nella vicenda delle mostre sperimentali ebbe inizio nei primi anni ’90, con un passaggio dalla critica collettiva a sperimentazioni più individuali che non si limitarono alle forme e ai mezzi espressivi artistici ma coinvolsero anche il modo di esporre e presentare i lavori. Anziché inseguire la rivoluzione sociale e il cambiamento, curatori e artisti cominciarono a dedicarsi alla creazione e al mantenimento di strutture che garantiscano regolari esibizioni d’arte sperimentale e minimizzassero l’ingerenza delle autorità.

I vari centri dell’arte contemporanea cinese seguirono, tra il 1997 e il 2002, percorsi assai diversi e determinati dalle circostanze locali. A Pechino gli artisti che si confrontavano con stili contemporanei non contemplati dalle accademie d’arte erano di fatto isolati dal potere politico ed economico. Questo relativo isolamento permise loro di sperimentare con una relativa libertà d’azione. Sul versante opposto, a Shanghai e nella provincia del Guangdong, gli artisti contemporanei cercarono una qualche forma di supporto economico. Nelle provincie della Cina centrale invece, istituzioni come l’accademia d’arte del Sichuan rimasero strettamente connesse a un’espressione artistica ufficiale.

L’isolamento spinse molti artisti di Pechino a organizzare reti libere di comunicazione non ufficiale e a trasferirsi in aree lontane dal centro della città. Mentre a Shanghai la prima biennale d’arte autorizzata dal governo si tenne nel 2000, Pechino dovette attendere fino al 2002 per la prima esposizione di una certa ampiezza legittimata dalle autorità.

Nel frattempo il legame tra artisti e mezzi di comunicazione divenne più stretto. Già nel 1997 – è solo uno dei possibili esempi - un artista graffitista di Pechino, temendo l’arresto, coinvolse i giornalisti della stampa specializzata perché sostenessero la sua protesta: ciò che faceva non era vandalismo, era arte. Grazie a quegli interventi, i graffiti, una forma d’espressione ancora al centro di molte discussioni e interventi della polizia in Europa, sono abbastanza diffusi tra i ventenni cinesi e anche artisti riconosciuti quali Liu Bolin citano questo tipo d’arte urbana nei loro lavori.

I centri di creazione dell’arte contemporanea cinese cambiano continuamente: il mercato dell’arte cinese è notoriamente molto aggressivo, ma vi sono, per contro, pochissime risorse per la sperimentazione e produzione artistica non a fini commerciali. L’occasionale intromissione del governo, l’intervento straniero, la politica, svariate posizioni critiche, numerosi trends artistici locali e internazionali sono solo alcune delle forze che influenzano la produzione degli artisti cinesi. La sconfinata e ultra-moderna Pechino continua a ridefinire i propri confini per consentire alle sue comunità artistiche lo spazio sufficiente per espandersi. In anni recenti, infatti, la metropoli ha assistito alla nascita e distruzione, di numerosi e vasti quartieri artistici, e di interi distretti di gallerie, istituzioni culturali e musei.

L’ormai famosa serie di opere di Liu Bolin “Hiding in the City” fu inizialmente ispirata proprio dalla distruzione di uno di questi distretti, il Suojia Village a nord-est di Pechino, un tempo sede di un centinaio di studi di artisti.

Liu Bolin: vedere con il corpo

"Usare gli occhi non è un atto slegato dal resto del corpo. Vedere ed essere "(com)mossi", gesticolare ed elaborare immagini visive sono pratiche estetiche che si implicano a vicenda".

Carrie J. Noland, 2004

“Hide and Seek” è una mostra personale delle opere dell’artista cinese Liu Bolin che presenta lavori creati in due luoghi e momenti molto diversi ma che hanno numerosi punti di contatto. Una parte delle opere, create a Pechino, riflette la percezione che l’artista ha del proprio contesto sociale, e la sua costernazione davanti al brutale, talvolta assurdo, processo di urbanizzazione della Cina contemporanea. La nuova serie di opere ha come sfondo Verona, una delle più belle citès d’art italiane, dove Liu Bolin è stato invitato da Boxart come resident artist e dove ha indagato l’atteggiamento dell’Italia nei confronti del proprio patrimonio culturale e come la memoria umana e architettonica segnano il paesaggio.

Liu Bolin è conosciuto soprattutto per la sua serie di foto di performance Hiding in the City dove, dipingendo scrupolosamente il proprio corpo e quello di altri individui in modo tale da fondersi e sparire in una varietà di contesti urbani, oggetti, e architetture, l’artista indaga i modi in cui i luoghi in cui viviamo danno forma alle nostre identità.

Artista multidisciplinare, che usa pittura, fotografia, scultura e performance, il tentativo di Liu Bolin è di individuare gli spazi tra libertà e controllo, l’espressione e il silenzio, l’individuo e la comunità, la presenza e l’invisibilità.

Gli sfondi scelti da Liu Bolin, siano essi monumenti o semplici muri, architetture, segnali stradali, slogan politici o cabine del telefono, sono dei significanti. Il loro significato resta aperto. Ed è proprio questa apertura che permette all’atto di stare in piedi di fronte ad essi, “nascondendosi” in essi, di esser letto come un tentativo di dialogo tra la memoria storica e l’esperienza personale.

Le immagini elaborate al digitale sono divenute un fenomeno culturale diffuso nella nostra era mediatica, onnipresenti al pari di materiali e oggetti della produzione industriale. Ma le immagini fotografiche di Liu Bolin, reminiscenti lavori quali le serie Tatoo di Qiu Zhijie's (1994-2000) e Family Tree (2000) di Zhang Huan, non sono il prodotto di una manipolazione digitale, ma di un competente uso di tecniche pittoriche unite ad un senso plastico dello spazio e del corpo umano.

Nato nel 1973 nella provincia dello Shandong, Liu Bolin si è formato alla prestigiosa Accademia Centrale d’Arte, dove è stato studente del noto artista Sui Jianguo, suo mentore agli inizi della carriera. La sua è la generazione che ha assistito ai grandi cambiamenti dei primi anni ’90, quando la Cina intraprese un cammino di rapida crescita economica e ottenne finalmente una, seppur ancora relativa, stabilità. La progressiva accettazione delle regole del capitalismo ha lasciato dietro di sé molta disillusione politica e confusione intellettuale.

Le immagini pregnanti create dallo scultore/pittore/fotografo Liu Bolin invitano a riconsiderare gli spazi e i luoghi familiari, non importa se per l’incontro quotidiano con essi, o perché osservati al cinema o in televisione. La ripetizione delle sue azioni di camouflage con cose e persone della vita quotidiana conferisce nuovi significati ad azioni precedenti, così come ai luoghi dove si sono svolte. Una testimonianza silenziosa, ad occhi chiusi, il tentativo umano di accettare e adattarsi ad ogni situazione. Nei lavori mimetici di Liu Bolin si assiste ad una moltiplicazione senza fine dello spazio e degli oggetti. Dov’è quel manifesto? Quando ho già visto quel palazzo? Si tratta dunque di riflettere sull’arbitrarietà, l’incertezza e l’incommensurabilità degli spazi urbani cinesi.

La serie dedicata ai Giochi Olimpici, con il suo comico disvelamento della vacuità dell’immagine pubblica di una Cina come nazione moderna e di successo, pone l’accento con ironia l’uso retorico delle immagini, dietro cui si cela il tentativo di creare consenso, omogeneità culturale e conformismo.

Sarebbe sbagliato desumere che il mostrare le fratture nel presunto armonico dialogo culturale cinese si limiti alla mera sfera dell’urgenza artistica. Piuttosto, essa ha profonde implicazioni politiche, perché pone degli interrogativi sul tema dell’autorità istituzionale, e sulla retorica dell’identità culturale e nazionale che sottende ai miti del consenso e della collettività sociale. Il fardello patologico degli individui è confrontato direttamente con quello di una società intera invischiata nelle contraddizioni della propria identità culturale.

Gli artisti cinesi contemporanei utilizzano strumenti e media diversi per indagare la condizione esistenziale di costante cambiamento in cui essi vivono. La globalizzazione li ha portati in contatto con l’arte contemporanea occidentale, ma il loro sguardo rimane strettamente legato alla Cina. “Nel momento in cui l’infrastruttura fisica e psicologica della Cina viene smantellata, scrive Liu Bolin, si costruiscono nuove strutture. Nessuno di noi sa per quanto ancora dureranno le vestigia del nostro passato”.

Se l’arte può conservare un significato all’interno dell’universo di ribellione di Liu Bolin è nel suo essere un luogo di comunicazione, un luogo in cui ogni facile consenso non è ipotizzabile, e nemmeno allettante.

Quando mimetizzarsi è una strategia

Liu Bolin

Gli esseri umani sono animali?

Il camaleonte ha la straordinaria prerogativa di cambiare colore per uniformarsi al colore dello sfondo come forma di auto-protezione. Il serpente a sonagli può seppellire la maggior parte del proprio corpo nella sabbia. Non solo per proteggere sé stesso, ma anche per procurarsi il cibo. Molti altri animali, come gechi e scarafaggi hanno imparato a mimetizzarsi con l’ambiente esterno per affrontare il nemico nella lunga lotta tra vita e morte; la capacità di nascondersi è spesso il fattore più importante per la sopravvivenza.

Gli esseri umani non sono animali Perchè non sanno proteggere se stessi.

Due cose sono emerse chiaramente durante gli ultimi tremila anni di storia umana.: Primo, la specie umana progredisce distruggendo l’ambiente circostante; secondo, lo sviluppo degli esseri umani è costellato di orribili sfruttamenti. Il prezzo di questa brillante civilizzazione umana è che l’uomo dimentica quasi di essere un animale, dimentica di avere degli istinti.

Gli esseri umani sembrano aver scordato di dover ancora pensare a come sopravvivere. Mentre l’umanità si gode i frutti del proprio progresso, scava la propria tomba con la sua ingordigia. Nella società umana non è sufficiente mimetizzarsi per sopravvivere. Il concetto di umanità stessa è messo a repentaglio. Invece di affermare che la specie umana gioca un ruolo dominante, sarebbe meglio dire che gli umani si stanno lentamente rovinando con le proprie mani.

Lo sviluppo economico ha complicato il significato della parola umanità. Con la morte sparisce il corpo ma i cambiamenti economici stanno indebolendo lo spirito degli esseri umani. Visto che il pensiero è sinonimo di vita questa è una morte ben peggiore dell’altra. La guerra nella prima parte del secolo scorso e il progresso economico della seconda metà del secolo hanno indebolito la capacità degli esseri umani di creare significato. Consapevolmente o meno coloro che si consideravano i padroni della terra sono in balia delle forze della natura

Alcuni comportamenti umani servono ad illustrare questa tesi.

Un secolo fa ogni uomo cinese portava una lunga treccia sulla schiena. A quel tempo era normale. Se un uomo non portava la treccia o la tagliava, ciò era sinonimo di possedere idee progressiste. Ma ora la treccia dietro la nuca che era diventata il marchio degli artisti, recentemente è prerogativa dei parrucchieri, derisi dalla maggioranza della persone che portano i capelli corti. I capelli lunghi e la treccia in sé non hanno alcun significato. I loro significati dipendono dall’ambiente esterno. Gli esseri umani nascono all’interno della società, e i nostri pensieri sono spesso determinati dalla cultura comune. Gli esseri umani sono così deboli che persino i loro pensieri saranno copiati inconsciamente dalla prossima generazione.

Il lavaggio del cervello è più terribile della sparizione fisica.

Ogni tanto mi considero fortunato di non essere nato durante gli anni ’50. La gente di quella generazione ha visto di tutto. Loro hanno avuto molte esperienze comuni: subire il fascino del Presidente Mao, la rivoluzione culturale, un’educazione anomala, non andare a scuola, ricevere una coppa di ferro di riso ma andare incontro all’ondata di licenziamenti, la soppressione della distribuzione delle case, iniziare a comprare le proprie abitazioni, i figli che vanno a scuola a proprie spese e così via. Semplicemente il potere della cultura e della tradizione può influenzare il pensiero di un’intera generazione.

Oggi esistono molti differenti modi di pensare. Ogni persona sceglie la propria strada nel venire a contatto col mondo esterno. Io scelgo di fondermi con l’ambiente. Invece di dire che scompaio nello sfondo circostante, sarebbe meglio dire che è l’ambiente che mi ha inghiottito e io non posso scegliere di essere attivo o passivo.

In un contesto che privilegia l’eredità culturale, il mimetismo non è di certo un posto sicuro dove nascondersi.

opere

120x75 cm

2006

Cod. 22

120 x 75 cm

2006

Cod. 15

90 x 90 cm

2008

Cod. 3

120 x 120 cm

2008

Cod. 4

120x120 cm

2008

Cod. 5

120 x 120 cm

2008

Cod. 7

120x120 cm

2008

Cod. 6

130 x 160 cm

2006

Cod. 76

66x200 cm

2006

Cod. 13

118 x 150 cm

2007

Cod. 12

63x80 cm

2007

Cod. 11

63x80 cm

2007

Cod. 23

95 x 120 cm

2007

Cod. 10

95x120 cm

2008

Cod. 9

79 x 120 cm

2006

Cod. 16

63x80 cm

2008

Cod. 8

140 x 100 cm

2008

Cod. 2

250 x 200 cm

2008

Cod. 1

120 x 90 cm

2007

Cod. 21

120 x 90 cm

2007

Cod. 20

120x90 cm

2007

Cod. 19

120x90 cm

2007

Cod. 18

130 x 30 x 20 cm

2006

Cod. 33