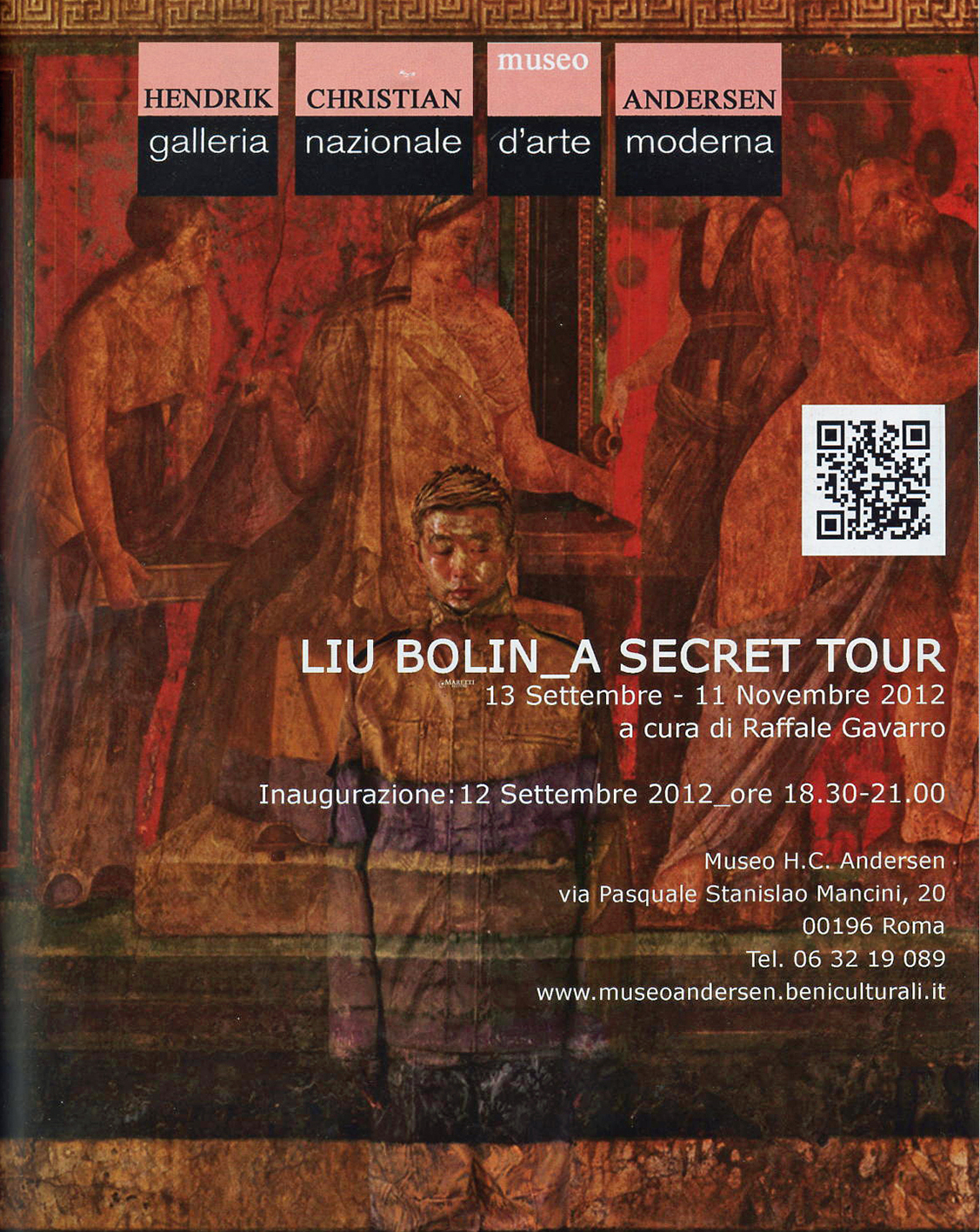

Liu Bolin. A Secret Tour

Curata da Raffaele Gavarro

Dal 13/09/2012 al 11/11/2012

Museo Hendrik Christian Andersen, Roma

Museo Hendrik Christian Andersen, Roma

Il Museo Andersen e la mimesi

di Matilde Amaturo

La casa museo di Hendrik Christian Andersen ospita la significativa esposizione di Liu Bolin, dal titolo A Secret Tour, l’artista cinese che si fa riprodurre in modo mimetico rispetto al luogo in cui si trova, scomparendo, e dando quindi una lettura simbiotica di sé in rapporto alla struttura decorativa e architettonica a cui si appoggia, proponendo la riflessione della figura umana e la sua localizzazione antropica.

La molteplicità dei luoghi in cui si pone induce quindi lo spettatore a uno sguardo indagatore nelle profondità estetiche e interiori dell’essere.

L’opera dell’artista cinese si presenta come una progressiva tecnica operativa che si avvale, per la produzione finale, di body-art, performance, pittura e fotografia.

In tutte queste fasi è rintracciabile un nucleo vitale di partenza: il ritratto di sé, dell’individuo e del luogo in cui si trova.

L’autoritratto è soggetto caro a tutta la pittura italiana e come ci narra Plinio è all’origine della storia dell’arte, a questo leitmotiv appare dedicata anche l’originale e unica esposizione romana di Liu Bolin al museo Andersen.

La tematica del ritratto e dell’architettura diviene curioso accostamento alla dimensione domestica e allo stesso tempo monumentale delle opere di Hendrik; appaiono vivi i suggerimenti creativi fatti di presenze mimetizzate nella struttura decorativa e architettonica dell’edificio. Nella decorazione dell’edificio realizzato su disegno dell’artista dal 1922 al 1924, si scorgono all’esterno medaglioni dal gusto neo quattrocentesco mescolati a motivi musivi e a elementi naturalistici che celano i ritratti dei familiari dello scultore, a perenne ricordo della loro presenza in quei luoghi.

Le collezioni del museo sono ricche di disegni, ritratti di amici e parenti di Hendrik Andersen, poi anche centinaia di cartoline e foto databili tra la fine del XIX secolo e i primi decenni del Novecento, che ritraggono i volti di personaggi celebri della cultura italiana e americana a Roma, scandendo spazi esterni e dimensione privata. Da Henry James a Tagore, da Umberto Nobile a Sibilla Aleramo, da Ronald Sutherland Gower a Maud Howe Elliot, indelebile anche se mutevole presenza dell’artista e del mondo che lo circonda a Roma, in Europa, in America.

Nel 1898 Hendrik Andersen si ritrae alla nazzarena, con caratteristiche fisiche modificate, barba e capelli lunghi, secondo il gusto dei pittori romantici di primo Ottocento che a Roma si prefiguravano come seguaci della pittura del Quattrocento fiorentino e in particolare raffaellesca.

Questa moda coincide con i gusti coevi di molti pittori americani innamorati dell’arte italiana, come già Sargent aveva fatto a Firenze, e sono testimonianza di una significativa certezza di mimesi nel passato preso a modello, a mascheramento di se stessi, nella continua ricerca di esemplari a cui far riferimento e con cui confrontarsi.

Il nuovo che cerca continuità nel passato, ma nello stesso tempo traveste, si trucca per apparire ora come allora in uno scambio tra culto per le testimonianze della storia e voglia di rinnovamento.

Il ritratto quindi come pretesto, memoria più o meno evidente, racconto rivelatore non solo di avvenimenti ma di stati d’animo, testimone dei viaggi nel tempo e nei luoghi, ancora attualissimo tema della presenza dell’uomo moderno nel suo rapido muoversi, evolversi, costretto a tramutarsi nella difficile dimensione di straniero.

Nella realtà senza soluzione di continuità

di Raffaele Gavarro

La prima idea che mi è venuta in mente guardando il lavoro di Liu Bolin, e conoscendo naturalmente il modo con cui realizza le sue immagini, è stata quella relativa alle possibilità ancora sorprendenti del low tech, o se preferite dell’analogico, nell’epoca di una digitalizzazione che è diventata del tutto naturale e grazie alla quale la verosimiglianza raggiunta dalle immagini è ormai pressoché perfetta.

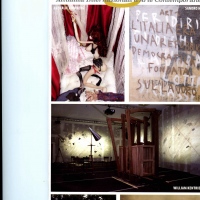

E in effetti, questa dialettica tra bassa e alta tecnologia è un aspetto che salta subito agli occhi. L’impatto apparentemente hi tech della mimetizzazione è appunto neutralizzato dall’informazione sul non meno sorprendente processo pittorico manuale, per la precisione di body paint, grazie al quale Liu Bolin viene reso omogeneo all’ambiente in cui sceglie di scomparire. Una sparizione che risulta percepibile da un unico punto di vista, il classico punto di fuga, che è ovviamente coincidente con l’obiettivo della macchina fotografica. Questa prima impressione e relativa riflessione sulle possibilità delle vecchie tecnologie nei confronti delle nuove, o sulle relazioni ancora possibili tra entrambe è in realtà oltre che il frutto dell’iniziale sorpresa visiva, anche il risultato di una preferenza interpretativa che ha sempre posto l’accento sulla scomparsa di Liu Bolin nello spazio della rappresentazione. Lo spettacolare effetto camaleontico è però solo l’aspetto più appariscente di un gesto che invece ha a che fare con una totale immedesimazione con la realtà, e che necessariamente comporta un’affermazione di appartenenza ad essa, ma che soprattutto cerca una modalità inedita di indagarla.

In più di un’occasione Liu Bolin ha dichiarato che l’origine di questo suo lavoro sulla mimetizzazione è stata la distruzione di un pezzo della sua realtà. Siamo nel 2005 e le autorità cinesi decidono di smantellare il Suojia Village International Arts Camp di Pechino. Liu Bolin reagisce decidendo di mimetizzarsi tra le macerie di quello che era il suo studio, diventando parte di quelle rovine. L’azione performativa e la foto che la testimonia, rappresentano un’attestazione inequivocabile del suo essere parte di quella realtà, e il silenzio di quell’immagine dice molto di più di qualsiasi contestazione rumorosa e variamente argomentata. Liu Bolin indica, senza possibilità di essere frainteso, che la demolizione fisica del luogo comporta anche l’inevitabile distruzione di quello che il luogo contiene e rappresenta, fino alla sua stessa identità di uomo e di artista. La realtà è data così in tutta la sua complessità, che è tanto del suo essere oggettiva – la cosa è lì, ha quella forma ed è fatta di quella materia. Prima era integra, ora è distrutta -, quanto della soggettività che la abita.

Proprio con Suojia Village del 2006 prende il via la serie di performance/foto che vanno sotto il titolo generale di Hiding in the city e che porteranno Liu Bolin ad immergersi dentro diverse realtà.

Tra le prime opere di questa serie c’è un’immagine, anch’essa del 2006, che indica con grande chiarezza la consapevolezza con la quale Liu Bolin si pone dentro la complessità della realtà. Si tratta di N°1 Tien An Men Square, in cui il corpo di Liu Bolin dipinto si sovrappone ad un punto preciso della piazza, mentre il suo volto, non truccato, coincide con quello di Mao Tse Tung nel grande ritratto esposto su Piazza Tien An Men. È un lavoro che ovviamente parla dell’identità dell’individuo e del popolo cinese, utilizzando un tono assertorio e del tutto antiretorico, esattamente contrario a quello che la tipologia del ritratto del leader e la sua collocazione sulla piazza impongono. Nel sovrapporre il suo volto a quello del Presidente Mao, Liu Bolin compie solo in apparenza un atto di identificazione, che è quello richiesto dalle autorità, e per la verità ancora desiderato da molti cinesi, realizzando di contro un atto di differenziazione, o meglio di aggiornamento non solo della tipologia del cinese, ma anche delle sue aspirazioni.

La questione di quanto queste immagini esprimano un impegno e una riflessione sugli aspetti politici e sociali della Cina e non solo, è chiaramente un argomento non secondario nel nostro ragionamento. Le parole di Liu Bolin su questo punto non sono mai state risolutive in un senso o nell’altro. Definisce le sue performance e le immagini che ne seguono delle social sculptures, ma poi ne nega una priorità antagonista. Liu Bolin nasce proprio come scultore, e di fatto non ha mai smesso di esserlo. In tal senso alcune sue sculture tridimensionali, come Fist, un gigantesco pugno in ferro del 2006, di cui esiste anche una versione in vetroresina dall’esplicito colore rosso, o la serie dei personaggi in vetroresina con le mani rosse, Red Hand, ma anche i Red Skull del 2008, sono facilmente riconducibili ad una posizione critica nei confronti del potere. Non di meno da questo punto di vista si può leggere la divisa militare che Liu Bolin porta in tutte le sue performance d’immersione nella realtà. Una divisa che oltre ad essere uniforme, nel senso di universalmente conforme, rappresenta l’uniformità altrettanto universale di un potere che si costituisce come forza che oltre ad essere offensiva e difensiva, assume spesso carattere oppressivo.

Ma anche qui farei retrocedere la riflessione dall’evidenza delle immagini alla questione preliminare del rapporto con la realtà.

Nel porsi senza soluzione di continuità all’interno di essa, Liu Bolin coglie infatti una delle problematiche essenziali di questo tempo, in cui l’accezione di una realtà fatta di elementi concreti e di verità essenziali non eludibili sta riguadagnando terreno nei confronti di quella smaterializzazione del reale che ha conosciuto una sorta di apoteosi con il mito del virtuale. Oggi, o meglio da qualche anno, assistiamo infatti ad una vera e propria inversione di tendenza tanto nella riflessione filosofica che nell’elaborazione artistica. Direi che le ragioni di questo deciso cambio di rotta vanno dalla semplice insofferenza generalizzata verso quell’impalpabilità del mondo, che partito da una necessità di alleggerimento ha di fatto vanificato la nostra stessa capacità di modificarlo ed eventualmente di migliorarlo. A questo proposito un altro aspetto decisivo è la de-responsabilizzazione che quella presunta inconsistenza del mondo ha comportato. Una rinnovata richiesta di certezze riguarda infatti non solo la natura, il posto e la funzione delle cose, ma anche come e se esse sono utilizzate per il bene o per il male comune. Dichiarare la realtà conoscibile attraverso la semplice evidenza di ciò che è, comporta infatti anche l’inevitabile riconoscimento che la verità stessa è raggiungibile e condivisibile. Una cosa che si porta dietro una altrettanto raggiungibile e condivisibile oggettività etica. Dal momento in cui accettiamo la realtà come repertorio di cose che esistono prima e dopo la nostra possibile ed eventuale interpretazione, riconosciamo che quest’ultima non può modificare la sostanza delle nostre azioni, che nella realtà creano conseguenze anche quando non sono dettate da cause. Non si tratta di uno scontro tutto astratto ed accademico tra ontologia ed ermeneutica, quanto della necessità pratica che a quest’ultima sia tolto quel predominio che ha reso plausibile l’alterazione stessa della realtà. Il passaggio della realtà attraverso i media e la sua interpretazione che diventa nuova realtà, ci parla esattamente di questo tipo di conseguenza. Negli ultimi anni abbiamo spesso parlato di una compresenza di piani del reale, di quelli mediatici al fianco di quello della realtà-reale, dichiarandoli in definitiva tra loro mutuabili. Viene quasi da sorridere oggi di fronte all’ingenuità apparentemente sofisticata di quelle considerazioni. Perché appare improvvisamente chiaro che quello che vediamo nel monitor ha una relazione decisamente parziale con la realtà. Nel migliore dei casi ne è una rappresentazione verosimile, ma in nessun caso essa può darsi come surrogato se non in un senso di nevrotica percezione del mondo. È come dire, prendendosi davvero sul serio, che se lo si desidera è possibile sostituire l’internet time con il tempo biologico, per farlo basta stare connessi almeno dodici ore al giorno e il gioco è fatto. In effetti lo si potrebbe vendere come un buon sistema per combattere i radicali liberi. Ma a parte la facezia, meno improbabile per la verità di quello che appare, è esattamente questo che accade quando un’interpretazione della realtà sostituisce, ancorché ovviamente in modo temporaneo, il significato oggettivo, direi elementare, delle cose che sono semplicemente il reale.

Ma è necessario precisare che tutto questo discorso ha un senso nell’ambito della cultura occidentale e di quella che definiamo, o che si definisce, come occidentalizzata. Nel prologo del “Manifesto del nuovo realismo” (Laterza, 2012), che è giustamente considerato uno dei testi essenziali di questa riflessione sul ritorno alla realtà, a proposito di questo passaggio dall’ermeneutica all’ontologia come testimonianza della fine del postmoderno, l’autore Maurizio Ferraris dice: “Ovviamente, la svolta non ha solo una storia, ma anzitutto una geografia, circoscritta a quello che Husserl chiamava <>, all’Occidente di cui Spengler profetizzava il tramonto novant’anni fa. Difficilmente si può pensare a un postmoderno in Cina o in India.”.

Anche se bisogna aggiungere che è altrettanto difficile dire quale sia oggi con precisione la geografia dell’occidente, che appare sempre più come una dimensione culturale pervasiva e in grado di contaminarsi in modo più o meno profondo con le altre culture. E questo direi soprattutto nell’ambito delle arti visive. La Storia dell’Arte occidentale, nonostante nei luoghi non-occidentali risulti spesso immersa in una nebbia e in una vaghezza sorprendenti, non manca di lasciare tracce e produrre conseguenze tutt’altro che secondarie, prestandosi spesso ad innesti non prevedibili.

Anche Liu Bolin, con tutte le avvertenze del caso, è sicuramente dentro il perimetro di questa geografia culturale molto contaminata e direi oscillante. Una condizione che è ravvisabile ovviamente nella stessa formalizzazione linguistica delle sue opere, come accade del resto per quella di molti degli artisti cinesi contemporanei, ma che soprattutto si percepisce nel caso di Liu Bolin proprio nel momento in cui si confronta direttamente con la realtà occidentale.

In particolare nella relazione con la realtà italiana Liu Bolin è evidentemente condizionato dagli elementi più tipici e suggestivi della nostra storia e di tutto quello che costituisce il nostro ambiente che, prima di essere una realtà-reale, per buona parte del mondo è un’immagine. Ed è proprio su quest’aspetto che Liu Bolin calca la mano, ricercando quell’immagine nelle città e nei musei italiani e rendendola reale con la sua immersione fisica in essa. Ma soprattutto in questo modo Liu Bolin intende compiere una propria personale indagine sui fondamenti della cultura occidentale.

Per Liu Bolin l’Italia, la cultura artistica del nostro paese, rappresenta “la base della cultura europea”, ed è quindi come se decidesse entrando nella fisica realtà di alcuni dei suoi luoghi più rappresentativi, di partire dalle nostre radici per risalire fino all’oggi e cercare di capire chi siamo. Naturalmente per quello che ci riguarda la questione è doppia: scoprire quello che qualcun altro pensa di noi e non di meno, davanti a quelle immagini che ce lo raccontano, capire noi stessi qualcos’altro di noi.

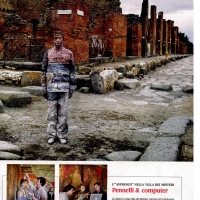

Il viaggio italiano di Liu Bolin è cominciato a Verona nel 2008, per poi proseguire a Venezia e Milano nel 2010, e giungere a Roma e Pompei nel 2012. Ultima tappa la Biblioteca Capitolare di Verona.

La scelta della location per Liu Bolin è un momento essenziale di tutto il suo lavoro. Stare in piedi per ore in un punto preciso, trovare i colori che creano esattamente la continuità tra sé e l’ambiente circostante, scoprire la luce, come cambia e in che ore e con che cielo diventa ideale. Ma anche capire qual è l’effetto del luogo con la sua presenza all’interno, cosa accade a quell’immagine, come si trasforma e quale senso acquisisce. Gli aspetti tecnici s’intrecciano con quelli concettuali, così come i linguaggi si alternano senza soluzione di continuità. Dalla pittura alla scultura, dalla performance alla fotografia. Ma anche all’interno di uno stesso linguaggio, il ventaglio delle possibilità espressive si allarga eludendo le classiche divisioni in generi. Si pensi alla pittura, che nel lavoro di Liu Bolin assume il carattere di quella del paesaggio, del ritratto, della natura morta, del trompe l’oeil, essendo al contempo un vero e proprio tableau vivant. In questa straordinaria capacità di sintesi e di rimessa in moto di tutta una serie di aspetti linguistici ed espressivi, si trova senza dubbio uno dei contributi più interessanti all’evoluzione linguistica che sta caratterizzando la ricerca artistica degli ultimi anni. Ma piuttosto che di eclettismo, nel caso di Liu Bolin pare più opportuno parlare di una sorta di coesistenza sincronica dei linguaggi in una forma e in un momento che sono appunto coevi. Un aspetto questo che assume un’evidenza ancora maggiore in un contesto di ambientazione artistica “classica” – le virgolette sono naturalmente d’obbligo -, in cui l’opera d’arte che qualifica la porzione di reale nel quale si immerge Liu Bolin determina un’inevitabile univocità di genere, che è data dalla sua storicizzazione nella nostra cultura visiva. La contraddizione che si crea tra l’opera “classica”, o l’ambiente “classico”, e l’alterazione imposta dalla presenza di Liu Bolin, è la causa della dinamica linguistica che caratterizza l’immagine finale, quella che veicola la nuova identità del luogo in cui si è immerso Liu Bolin e che si arricchisce di una contemporaneità tutt’altro che scontata. L’immagine diventa reale, testimonia il suo essere realtà, proprio grazie a questo scarto.

A proposito di realtà e di contemporaneità, una delle prime opere che Liu Bolin ha realizzato nel 2008 qui in Italia è stata UE Flag. Si tratta di se stesso dipinto davanti alla bandiera della Unione Europea. Ma più che una immersione, l’immagine sembra una sovrapposizione dei due elementi, di Liu Bolin stesso e della bandiera. Questa sensazione è rafforzata dal fatto che quest’immagine, e al momento solamente questa, è diventata un’opera tridimensionale, con l’artista riprodotto uno ad uno in vetroresina, naturalmente sempre di fronte alla bandiera di cui mantiene la colorazione blu del fondo e il giallo delle stelle. Ma non è tanto questo che volevo segnalarvi, quanto il fatto di come questo lavoro colga una serie di dati molto attuali, facendolo in un modo che è intuitivo e decisamente stringente. La crisi europea, che prima di essere finanziaria è una crisi evidentemente politica e quindi delle persone che nonostante si dicano europee, non lo sono tanto da appartenere ad una bandiera e viceversa, proprio com’è per l’immagine di Liu Bolin. Ma quest’opera è anche una sorta di omaggio cinese all’Europa, che racconta di una relazione che per l’Europa è diventata essenziale, com’è del resto anche di converso per la Cina.

UE Flag è il tipico esempio di come l’opera d’arte, quella di oggi come quella di ieri, riesce con un’immagine istantanea a cogliere la complessità del momento, disancorandosi dalla dimensione della cronaca e diventando emblematica delle dinamiche del tempo in cui è.

opere

250 x 200 cm

2008

Cod. 1

140 x 100 cm

2008

Cod. 2

90 x 90 cm

2008

Cod. 3

120 x 120 cm

2008

Cod. 4

120 x 120 cm

2008

Cod. 7

120x120 cm

2008

Cod. 5

120x120 cm

2008

Cod. 6

90 x 90 cm

2010

Cod. 30

90 x 90 cm

2010

Cod. 31

120 x 120 cm

2010

Cod. 29

120 x 120 cm

2010

Cod. 27

90 x 90 cm

2010

Cod. 28

Hiding in the Italy - Teatro alla Scala n°2

63 x 80 / 95 x 120 cm

2010

Cod. 43

90 x 90 / 120 x 120 cm

2010

Cod. 25

68 x 90 cm

2012

Cod. 35

90x120 cm

2012

Cod. 40

90x120 cm

2012

Cod. 38

68x90 cm

2012

Cod. 39

90x120 cm

2012

Cod. 36

90 x 120 cm

2012

Cod. 37

68 x 90 cm

2012

Cod. 34